Ecology and cosmology: rain forest

exploitation

among the Emberá

by William Harp

Paper

presented at:

Humid Tropical Lowlands Conference: Development Strategies and Natural

Resource Management, Panama, Republic of Panama, June 17-21, 1991

Published

in Nature & Resources, Traditional Knowlege in Tropical environments,

UNESCO, Volume 30, Number 1, 1994

Abstract:

The

protection and management of the humid tropical lowlands must involve the

participation of the peasant and indigenous cultures that exploit these fragile

areas. Small scale, indigenous,

lowland tropical rain forest cultures have evolved a complex system of cosmology

and subsistence technologies that have permitted hundreds of years of continuous

exploitation of the rain forest.

This

article explores how the Emberá, a lowland, tropical, rain forest culture that

practices subsistence horticulture, fishing, hunting and gathering, have

maintained, over many centuries, a system of exploitation and dynamic ecological

equilibrium that ensures the continuous availability of essential forest

resources. Political, economic,

technological and cosmological changes in the last two decades have disturbed

traditional patterns of exploitation. Land

managers can use indigenous knowledge and technologies as important factors in

developing planning polices.

Thesis

Tropical indigenous systems of thought

are complex systematic bodies of knowledge that categorize and describe

relationships between humans and their environment. These knowledge systems, difficult for western observers to understand,

are communicated through symbols, language, rituals, songs, music and narratives

and are imbued with a unique cultural character that unites people in an aura of

shared meaning and behavior. They

represent the accumulation of hundreds, if not thousands, of years of cultural

experience with forest dynamics, animals, plants and ecosystem phenomena and are

a virtual gold mine of information about the tropical rain forest. They

demonstrate a successful conservation model of low tech adaptation to the

forest.

The relationship between lowland,

tropical forest Indians and their environment has been a subject of great

debate. Are indigenous people the

caretakers of their environment, with culturally supported principals of sound

ecological management, or do they represent pioneering forces that herald the

vanguard of ecological destruction of the rain forest? Many people who have had casual contact with traditional indigenous

groups are often impressed with the efficiency and thoroughness that they

harvest and exploit forest resources.

The observer may be convinced that

indigenous inhabitants of the forest pose the greatest threat to its continued

existence. I agree that modern

technology and cultural change have created many unpredictable variables that

may support the thesis above. However,

in traditional societies, beyond any single individual's behavior, there is a

system of beliefs and attitudes that creates a super-personal, culture-wide

conservation ethic.

I propose that indigenous inhabitants

are caretakers of a sophisticated and systematic body of traditional, ecological

knowledge. Managers should pause to

consider the values these knowledge systems have to those who create development

strategies and guide natural resource management of the humid tropical lowlands.

Cosmology and beliefs

Which is most influential, cosmology

or behavior? I think that both are

mutually influential and co-evolve together. I agree with Reichel-Dolmatoff in that

"... cosmologies and myth

structures, together with the ritual behavior derived from them, represent in

all respects a set of ecological principles and that these formulate a system of

social and economic rules that have a highly adaptive value in the continuous

endeavor to maintain a viable equilibrium between the resources of the

environment and the demand of society." (Reichel-Dolmatoff, 1979)

Cosmology and belief systems in

small-scale societies serve to create a dense structure of information that

encapsulates a society’s belief about the nature of reality. The advantage of symbols and rituals is their effectiveness in

transmitting and communicating complex ideas in powerful and simple ways. These belief systems contain powerful images and concepts that affect

ecological relationships and incorporate strong ecological messages.

Subsistence technology

The Emberá have a highly evolved

subsistence technology with relatively high yield-to-unit-effort. They practice subsistence horticulture and depend upon fishing, hunting

and gathering from the adjacent forests and rivers. Each family, the primary unit of production, maintains a

variety of shifting and permanent horticultural plots. Their horticulture is highly diversified. They gather an impressive variety of edible or useful

products from the forest and areas surrounding their dispersed settlements and

villages. This provides

adaptability to ecosystem fluctuations where reliance on a few resources is a

risky business.

The Emberá farm three types of land:

shifting fields slashed-and-burned from the forest for corn and rice,

semi-permanently maintained plots for plantains and bananas, and permanent lands

adjacent to new and old homesteads where fruit trees and other secondary crops

grow. Primary crops include

plantain, rice, corn, manioc and other root crops. Secondary crops include sugar cane, yams, avocado, mangos, citrus, beans,

guava, otoé, peach palm, pineapple, soursop, papaya, banana, peppers, squash,

zapote, tomatoes, cacao, tobacco, coffee, calabash, herbs, spices, ornamental,

magical and medicinal plants.

Shifting agriculture creates a mosaic

of ecological niches adjacent to homesteads. This mosaic is a gradation of plant communities ranging from cleared

settlements, new farmland, old homesteads, recently abandoned lands, older

second growth, heavily exploited forest and old growth forest. Traditionally, this has created greater biological diversity

adjacent to habitation areas. This diversity attracts game animals.

Agricultural activities commonly require about one to two person-days a week

from each adult member of the family. A

garden of approximately two or three hectares of mixed crops (rice, corn,

banana, tubers and tree crops) would optimally provide for the average family

caloric subsistence needs and create a small surplus for sale or trade to

neighbors or the nearest town. Every

family needs a small amount of cash to buy essential food items, clothes and

hardware.

Wild and domesticated animals provide

the essential protein. They keep

chickens, dogs, ducks and sometimes pigs, cats and tamed wild animals. Riverine resources and game animals provide primary sources of protein. They exploit turtles, fish, crabs, freshwater shrimp, crayfish, mussels

and other shellfish. Preferred game

include deer, wild pigs, agouti, paca, curassow and guan. Less preferred but regularly eaten animals include iguanas, squirrels,

monkeys, toucans, parrots, macaws and doves.

Gathering from the old growth forest

provides plant products: fruit, nuts, firewood, construction materials (poles

and thatch) basketry materials, lianas for rope, carving wood, trees for

dugouts, fish poisons, body paints, pitch for glue, palm oil, medicinal,

hallucinogenic and magical plants and many other plant-derived materials.

Fertility

control

Emberá informants say their ideal

family structure would to be to have three or four children (preferably two boys

and two girls), enough to help with family labor and to provide family alliances

and cooperative work-mates when grown. Too

many young children would strain the production capability of the family unit. Pregnancy and birth are very sensitive times for the family. The mother and father of the child are required to observe a complex of

restrictions to avoid angering the forest spirits. The Emberá have a sophisticated system of birth control

through the use of anti-contraceptive and abortive plants. Much of their fertility control technology seems very

effective.

Most ritual activity is programmed

around the lunar cycle during the new and full moon. These activities invariably include restrictions on sexual intercourse

when women are most likely to be ovulating. If illness or lack of protein resources affect the family, a sign of

difficult times, the sexual restrictions associated with the ritual activities

of solving these problems will diminish the chances of getting pregnant.

Dispersed settlement

The Emberá maintain a dispersed

settlement pattern with a tendency towards neo-local and shifting residence. Emberá live traditionally dispersed along upper lowland

rivers in single or several households. The nuclear family, the basic social

unit, consists of a husband, wife and their children and may alternately contain

grandparents and married children. However,

married children, after the birth of their own children, tend to form their own

households. The Emberá value

privacy and build houses along water sources, preferably out of sight and sound

of any neighbors.

A house is abandoned if an adult

member of the family dies in it, as the living are disturbed by the visits of

the deceased soul as it returns to haunt the places it knew when alive; this

insures a continuous pattern of shifting house site locations.

The most important variable of Emberá

settlement patterns is that they are dispersed laterally along the rivers. Within the past two decades due to pressure by the national government

and missionaries along with the desire to benefit from promised government

programs the Emberá have grouped together in small towns. This process of village formation is articulately discussed by Herlihy

(1986).

If settlements grow too large, it

becomes difficult to acquire the necessary domestic resources and social

tensions increase along with a concomitant threat of supernatural invasion. Most families maintain two residences, one near a settlement

and one adjacent to their horticultural plots or old homestead. When social tensions increase in the village, families retreat to their

homesteads.

Flexible social rules

The Emberá have flexible social

rules, especially concerning residence, inheritance and child rearing. Recent biological research has shown that the lowland

tropical forest is much more dynamic than previously thought (Hubbell, 1990). Small scale egalitarian societies with relatively small dispersed

populations by necessity must be flexible in their patterns of resource

exploitation in order to cope with this dynamic environment. Social rules concerning residence, inheritance and personal relationships

must not be too strict as to prohibit potentially adaptive behavior. The post-marital residence options include neo-local residence, living

near ones in-laws, transience, maintaining more than one residence and urban

residence. The choice depends upon

three major categories of factors: kin and social relations, access to lands and

goods and fear of sorcery or spirits. Husband,

wife or children may inherit old homesteads and farmlands, but lack of fixed

rules may cause dissension among siblings. Children may be raised by the grandparents, especially if the mother is

quite young and not married. Children

are often given away to other families to raise as their own.

Egalitarian social structure

Traditionally, the Emberá have a

strong egalitarian social structure with no political or full-time craft

specialization. The egalitarian

structure of Emberá decision making ensures that each family functions as the

decision making unit. Community

activities are voluntary and group consensus determines community decisions. This egalitarian society emphasizes individual and family rights and

responsibilities and traditionally recognizes no formal tribal or community

authority. As an egalitarian

society, the Emberá have strong social sanctions about accumulating large

amounts of disposable wealth. This

creates jealousy among one's neighbors. Greed

and unusual wealth attract potentially malignant forest demons which bring bad

fortune.

Within the last fifteen years a system

of political representation of tribal chiefs, or caciques, has evolved. This system, partially

based on the successful Cuna political hierarchy, has been active in

negotiations with the Panamanian government concerning Indian affairs, land

claims and jurisdiction rights. Because of the egalitarian tradition, decisions

negotiated by the caciques are not

seen as universally binding by all Chocó.

Ritual drinking reduces social tension

and resolves conflicts. Families

within a community sponsor drinking parties where chicha (fermented corn mash)

is consumed in large quantities, resulting in the inebriation of most adult

participants. These drinking

parties create a social catharsis; personal tensions can be released through the

symbolic death and rebirth associated with getting drunk until unconscious.

Fear of sorcery and forest spirits

Natural elements, spirits, demons,

souls of the dead, animal spirit masters and the manipulation of spiritual

powers form the pivotal concepts of Emberá religious beliefs. These beliefs, viewed as supernatural by western observers, are seen by

the Emberá as co-extensive and an integral part of the physical domain. Everything is imbued with spirit. Animate and inanimate things alike have

spirit masters, a wandra, that

represent their spirit and natural essences. These spirit creatures, often ambivalent to human affairs, can be

manipulated through human intention to dispatch human desires and achieve human

goals.

Thus wandras,

primarily represented by animals, plant and demonic spirit masters, symbolically

encode a rich system of communication whereby the actions and characteristics of

these wandras represent specific

environments within the forest. Wandras are alive,

which means that all things plant, animal and mineral are controlled by a a

sentient being, potentially subject to human intention, but with their own

agenda tied to their own unique character.

The greatest fear of the Emberá is

the threat of sorcery of jealous from disgruntled neighbors, acquaintances and

shamans or the retribution of offended forest demons. Good hunters should observe a large number of prohibitions, including

sexual and dietary restrictions, in order to attract game animals and not offend

forest spirits. Successful hunters

must balance the need for meat against the jealousy and fear of the forest wandras that control the forest resources.

Reliance on shamanic power

The shaman is caretaker of the

esoteric supernatural knowledge. When

things go wrong (sickness, lack of success in hunting, spirit fright, crop

failure or even an abnormal number of snakes near house sites) an individual or

family seeks the assistance of a shaman to diagnose the supernatural cause of

the problem. He also incorporates

his person knowledge of the social context of the problem into his analysis.

Through the use of chanting,

psychoactive plants or alcohol, he enters into the spirit domain where he can

harness supernatural power to achieve human goals and seek specialized guidance

or information about human affairs from his spirit helpers. The spirit world is fickle, always on the verge of going out of control

or of controlling the shaman instead of vice versa, just as ecological events

essential to human welfare are delicately balanced.

Shamans, to affect a

cure, must cast out the offending spirit or spirit substance. This malignant supernatural material is normally sent to its originating

source, usually another shaman. Therefore,

all curing is sorcery to someone else or another community, and supernatural

energy flows from one settlement to another in a continuous cycle. Shamans then exist in a delicately balanced network of dynamic

supernatural tension. Under normal

circumstances of relative tranquility, the balance is maintained and populations

are in balance. I f the balance is upset, the supernatural consequences result

in serious social disruption.

Strong narrative tradition

The Emberá have a strong narrative

tradition that communicates ecological principles. The Emberá tell many stories that chronicle the acts of the Indians,

animals and spirits. The stories

contain strong evocative images and symbols and form a type of encapsulated

language, coding metaphorically the actions of the human and spirit world. This language with, its ecological imagery, shows what happens when the

cultural rules are broken and they delineate the fine line between the cultural

and spiritual domain.

Supernaturally protected areas

The Emberá recognize large

supernaturally protected areas in upper watersheds and along the spines of

mountain chains. These large

cachements of old-growth forest provide a relatively protected area for the

reproduction of faunal resources and protection of watersheds. Hunters usually journey no more than a half a day from their house sites

or dry season campsites. They have

little desire to spend the night away from their dwelling or prepared campsite,

as supernatural beings pose a serious threat. Spirit-animal patrols are quick to respond to human intrusions within

their domain and if they catch a human intruder they promptly pounce on him and

eat him.

Conclusion

The Emberá control their population

densities and maintain ecological stability through:

|

subsistence

technology

|

|

fertility

control

|

|

settlement

patterns

|

|

flexible

social rules

|

|

egalitarian

social structure

|

|

fear

of sorcery and forest spirits

|

|

reliance

on shamanic power

|

|

strong

narrative tradition

|

|

supernaturally

protected areas

|

This indigenous knowledge system

encodes a wide variety of ecological information and a highly evolved,

successful, low-tech model of environmental adaptation in the tropical rain

forest. It stands on the brink of an intellectual eclipse by western

influences. This eclipse, acutely felt by all of the world's small-scale

traditional societies, is the social equivalent to the loss of biological

diversity with its attendant path of ecological self-destruction.

These types of models may have

applications in management of protected areas where there are existing

populations of indigenous and peasant people. Stewardship of tropical lands extracts a high social price if we ignore

the rights of local people to their livelihood and self-determination. Cooperation with local people in managing protected forest areas and a

sympathetic understanding of the value of their knowledge systems will help

ensure the success of administrative and management programs. Separation from traditional technologies and land use will force

indigenous groups to move from self-sufficient net producers to wards of the

state. The impact of acculturation

and the rapidly disappearing rain forest both conspire against the traditional

cultures that have lived in this unique environment.

The social value of the knowledge

systems of these cultures is obscured by the difficult process of interpreting

the native point of view into something meaningful to Western observers. A fundamental understanding of the native point of view is an elusive

goal punctuated by frustration, contradiction and suspense of "scientific

objectivity." It requires an

emotional embrace as participant and the ethos transcendence of the observer. Each role provides its portion of contradiction, but, both are essential

to the goal of fundamental understanding.

The aware observer must be willing to

employ the powerful tools of science and intellectual discipline and yet suspend

one's strongly held beliefs to glimpse the equivalently empowered

"other" whose system of knowledge provides a different, yet

ecologically successful system of thought attuned and consonant with local

knowledge.

Tropical rain forest Indians similar

to the Emberá, through the power of symbols, rituals and belief systems, have

managed the forest well and benefited from the diversity of its products

throughout millennia of stewardship. They

have achieved dynamic, adaptive, heterogeneous, self-regulating ecosystem

relationships; do our Western knowledge systems have the capability to carry on

this tradition?

Bibliography

Herlihy, Peter H., 1986,

A Cultural Geography of the Embera and Wounan (Choco) Indians of Darien, Panama,

with Emphasis on Recent Village Formation and Economic Diversification, Ph.D.

Dissertation, Louisiana State University

Hubbell, Stephen P. and

Foster, Robin B., 1986, "Canopy Gaps and the Dynamics of a

Neotropical Forest." In Plant Ecology:77-96. Edited by M.J. Crawley.

Oxford:Blackwell Scientific Publication

Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo,

1979, "Cosmology as ecological analysis: a view from the rain

forest", Man 11( 3):307-318.

|

.

Read an Illustrated Emberá Story:

Available in English, Spanish and Emberá

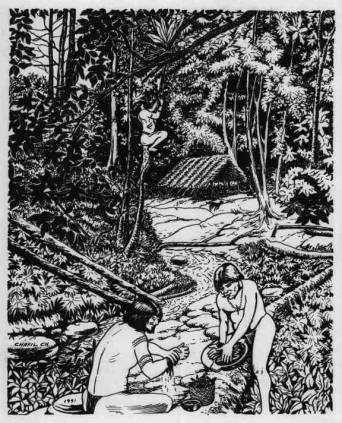

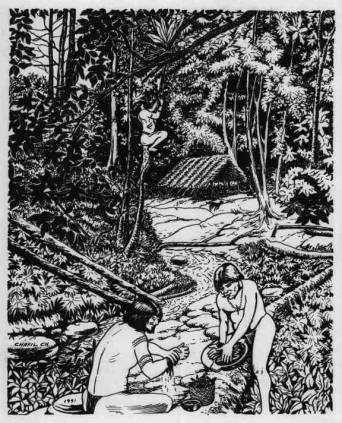

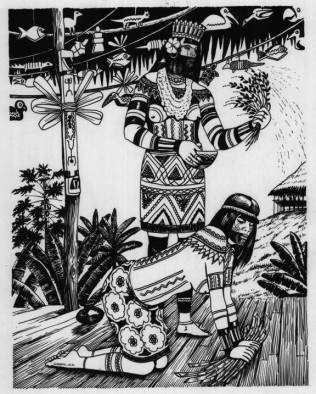

Figure

1 Havesting and preparing medicinal plants,

Illustration: Chafil

Cheucarma

© Copyright 1998, All rights reserved

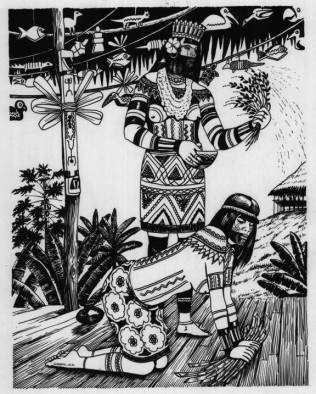

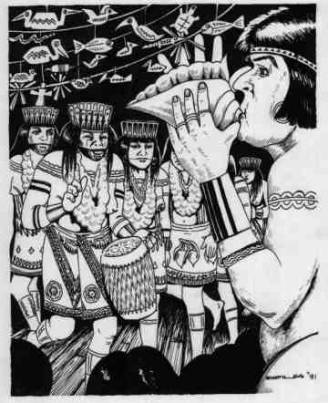

Figure

2 Ritual preparation for

a curing ceremony

Illustration: Chafil Cheucarma

© Copyright 1998, All rights reserved

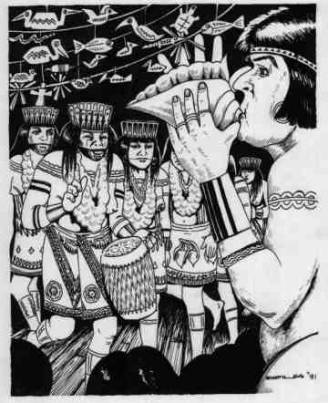

Figure

3 Shaman calling the

spirits as part of

a curing ceremony

Illustration: Chafil Cheucarma

© Copyright 1998, All rights reserved

|