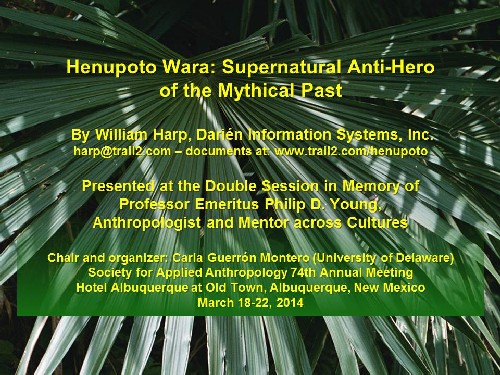

Henupoto Wara: Supernatural Anti-Hero of the Mythical Past

by William Harp, Darién Information Systems, Inc.

Presented at the Double Session in Memory of Professor Emeritus Philip D. Young, Anthropologist and Mentor Across Cultures

Chair and organizer: Carla Guerrón Montero (University of Delaware)

Society for Applied Anthropology 74th Annual Meeting

Hotel Albuquerque at Old Town,

Albuquerque, New Mexico March 18-22, 2014

Abstract:

The Emberá, a tropical lowland tribe of the Darién of Eastern Panama and the Pacific coastal lowlands of Colombia, have a strong tradition of telling detailed stories about animals, sprits, and demons and of adventures in the mythical past. Henupoto Wara, or Leg-Born Child, is one of the most famous stories and chronicles the adventures of this cultural anti-hero as he engages the many supernatural ecologies and denizens of Emberá cosmology. This paper presents the story and discusses an interpretation of some of the ecological images, assumed knowledge and cosmological implications embedded is this oft-told narrative.

Acknowledgements:

Philip Young was my academic advisor, mentor and friend. During the years 1979 -1986 I was a graduate and post –graduate student at the University of Oregon Department of Anthropology. After my student years, Philip and I stayed in constant contact over the decades and visited each other, especially in Panama. Of course, Philip never gave me a hard time that I did not become a full-time anthropologist as I cycled through many different careers. He mentored not just me, but also my wife, who was another U of O graduate student, and both my daughters when they pursued degrees and/or majors in anthropology. All of my immediate family came under his generous intellectual influence.

Before and during my activities at the U of O under Phil’s mentorship, I worked as an ethnographic researcher among the Emberá in the Darién of Panama (1976-1986) and of the large collection of ethnographic materials I collected and compiled, mostly traditional stories, I unfortunately published very little. I can but hope that Phil would have been pleased to know that of this collection, the well-know, traditional story of Henupoto, a fantastical, supernatural story of the Emberá cultural anti-hero, is the first to be published.

Collaborators:

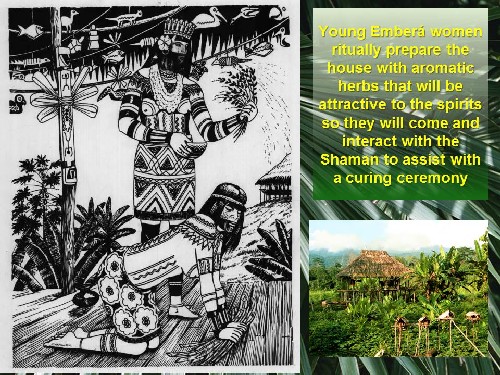

I would like to mention some of my many Emberá colleagues who assisted me along the way. In Manené, Karé Canasarí, forced me to continuously rethink Emberá cosmology as he generous permitted me to attend his curing ceremonies. His daughter, Enelda Cansarí (the maestra) and her sister, Alicia Cansarí, help me bridge the gap between their father’s world of spirits and my world of intellect. Rogelio Cansarí, Karé’s grandson, worked as a translator and assisted me to understand Emberá culture.

In Pijivasal, Alfonso the shaman took an interest in my education, and my adopted family of Pájaro, Cristina, Alipio, Teresa and Lucia Flaco were my constant companions in those years past. The brothers Serafín and José Contreras were my closest hunting companions to whom I am forever indebted for their friendship, interest and patience. And many thanks to the community members of Pijivasal and Manené so many years ago who patiently accepted my interest in their culture and graciously welcome my presence in their communities.

Daniel and Nilsa Castañeda, brother and sister, worked diligently on the translation work and helped me to understand the layers of meaning and assumed knowledge behind the words.

Fiona Smythe and Kirsty Oliveira, sisters raised in Panama and with a good knowledge of indigenous cultures and general ecology of Panama, translated Nilsa’s Spanish text into English. I feel that their hard work, combined with Nilsa’s translation, properly reflects the rhythm and narrative style of Alipio’s narration.

Of the many researchers I have met, most notable I have enjoyed many hours of late night conversations about Emberá and Wounaan culture with Julie Velasquez Runk, Ph.D.

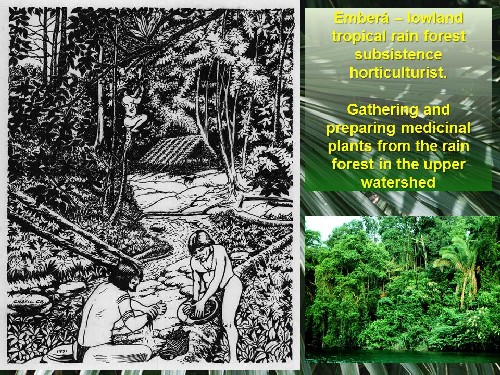

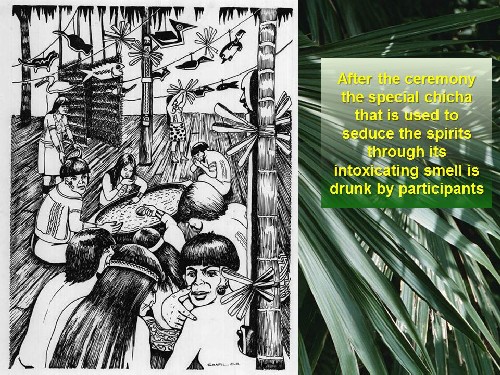

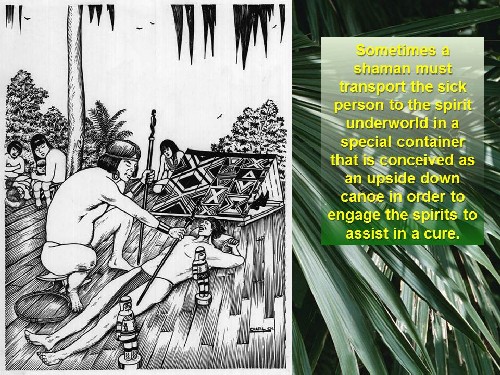

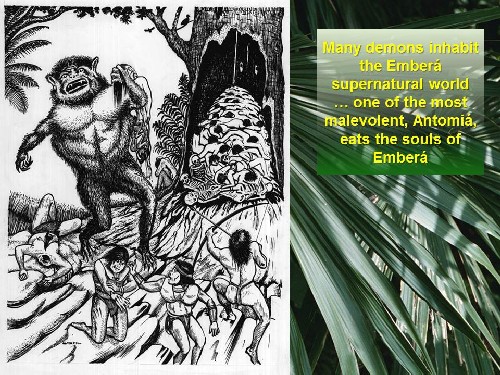

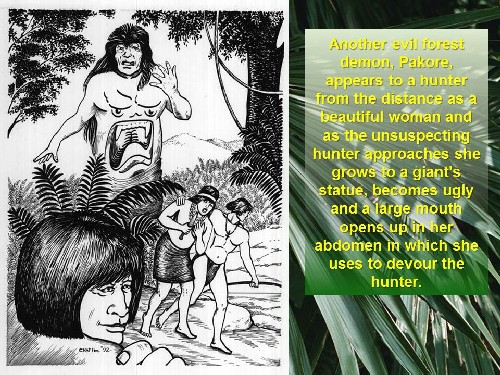

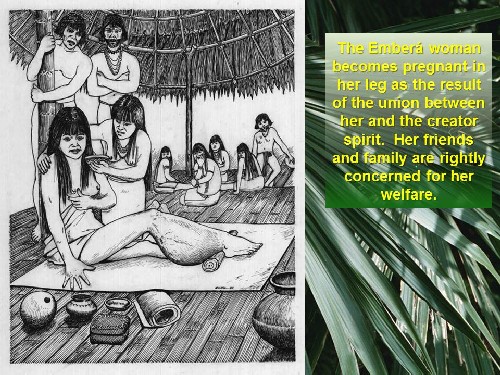

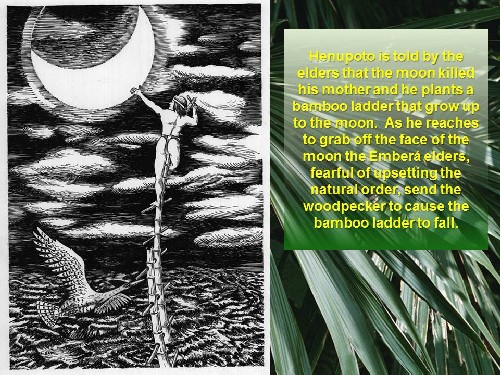

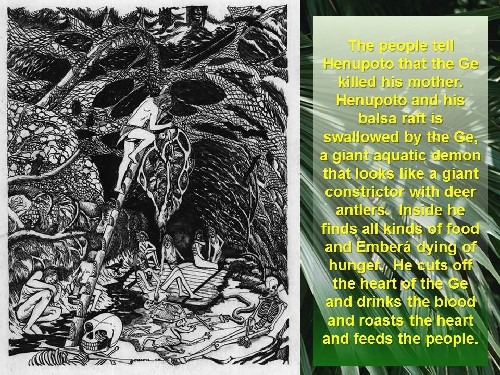

I would like to thank Chafil Cheucarama for contracting with me to create the wonderful pen and ink drawings. Although Chafil is Wouunan, he culturally shared many of the same or similar stories with the Emberá. His detailed artwork brings to life in exacting ethnographic detail the visual context of the stories, including Henupoto, that would otherwise be almost impossible to imagine.

And finally I would like thank the many Emberá who have so kindly given of their time to assist a rather slow and plodding researcher to appreciate the complex and difficult to understand details of Emberá cosmology in all its many manifestation of stories, rituals, ethnobotany, chanting, shamanic practices, subsistence, fishing and hunting technologies and processes of social interactions.

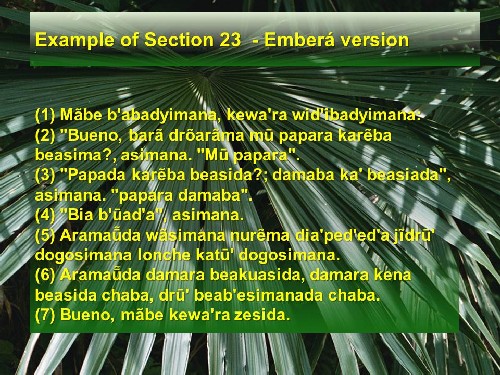

Versions and Organization of the Story

Note that the story is available in the Appendix in all three languages: Emberá, Spanish and English. I have artificially divided the story into sections, each section with a variable number of clauses or sentences that have sequential numbers for easy cross-referencing across the different language version. I will post this presentation and the three versions of the story at www.trail2.com/henupoto

Ethnographic Background

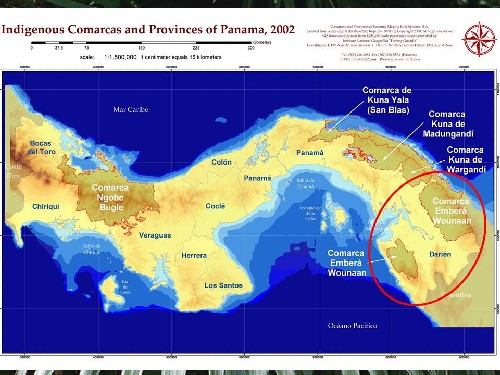

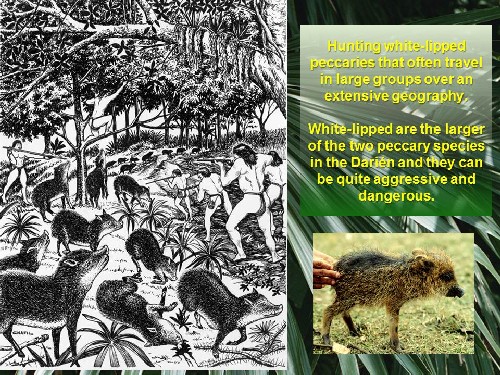

The Emberá traditionally live along the rivers, mostly the upper rivers, of the Pacific coastal lowlands of the Department of Chocó in Colombia and of the Darién Province in Panama. They are subsistence horticulturists who depend on fishing, gathering and hunting from the tropical rain forest. Socially and historically, they are egalitarian with little craft specialization or political hierarchy. They believe in spirits who live in and co-reside with the natural world.

They also believe in a mythical past in the early times when animals and their animal spirit masters talked and socialized with Emberá, and the spirit world was more visible and accessible to the average person. It is in this mythical past that the story of Henupoto takes place.

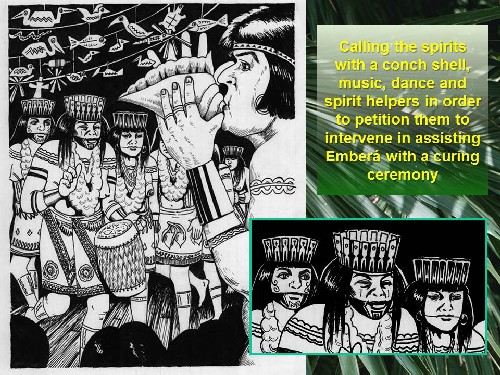

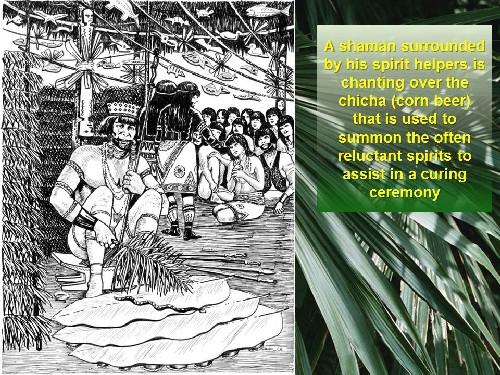

The Emberá have a sophisticated cosmology or, if you will, religion in which the many actors, spirits, demons, people, animals and natural forces interact in a complex and dynamic spiritual equilibrium. It is the role of the shaman to maintain this equilibrium by creating harmony among all these competing forces and to ensure that the spirits from time-to-time can be bound to human intention through carefully executed rituals that seduce the often ambivalent spirits into cooperation. I discuss the ecological implications of this cosmological perspective in a previous paper.

“The Emberá have a strong narrative tradition that communicates ecological principles. The Emberá tell many stories that chronicle the acts of the Indians, animals and spirits. The stories contain strong evocative images and symbols and form a type of encapsulated language, coding metaphorically the actions of the human and spirit world. This language with, its ecological imagery, shows what happens when the cultural rules are broken and they delineate the fine line between the cultural and spiritual domain.” (Harp, 1991)

The Context of the Story

The story of Henupoto is one of the most well-known stories of the pantheon of Emberá stories, myths, legends and narratives. It is the story of a man who is born of the union between a spirit and a woman. His mother dies in childbirth and he grows up a troubled but powerful orphan constantly trying to locate the being that killed his mother. As part supernatural being, he executes a series of herculean tasks that requires his special skills. Like many characters in stories among the Emberá, Henupoto is not precisely a hero but rather a supernaturally strong anti-hero that makes embarrassing demands upon society that results in the elders always trying to figure out a way to get rid of him.

However, no matter how difficult the task they assign or how unlikely he is to succeed at the tasks, he comes out victorious. That is, until the dramatic end. His efforts, it can be interpreted, profoundly protect society from the potential ravages of the supernatural world. Henupoto is constantly upsetting and resetting the balance between the human, the natural and the supernatural worlds. Although Henupoto is universally admired among the Emberá, for his strength, cunning, skill and determination, he is also an outcast and a cosmic misfit. He is also comically naïve as he attempts to track down the being that killed his mother when it was he, himself, when he was born, who caused his mother to die in childbirth.

The Narrator

This story was told by Alipio Flaco, in 1986 in Pijivasal, Darién. He is currently a ANAM forest guard in the Darien Biosphere Reserve. At the time of the narrative, Alipio was about 18 years old. He is surrounded by family, his two younger brothers, two younger sisters and mother and a few close friends, and it is in the evening after supper, which is the traditional time to tell stories like Henupoto. I was very pleased that Alipio told, with strong oratory skill, such a detailed, well-executed and comprehensive version of the story. Even so, in all its details it does vary from other versions of the story told in other locations or by other narrators.

It is traditional for one or more persons to function as the question person in order to add emphasis to the story. With leading questions and exclamations, this person or persons are incorporated into the story line.

A Delicate Balance in Mythical Time

In many ways, Emberá culture is about maintaining balance in order to ensure that forces do not spiral out of control. This delicate balance that represents the forces of the natural world, the world of spirits and social reality is clearly a major theme of the story. Henupoto acts in so many inappropriate ways, yet he is clearly assisting the Emberá to defeat their traditional enemies in the mythical past and liberate the gifts jealously guarded by these spirit demons.

The concept of mythical time is also difficult to appreciate. It is as if Henupoto was here yesterday but the elders say it was a time before their grandparents. On the other hand, it would not seem impossible to some Emberá that Henupoto walked the earth in recent years in some little know river in the Department of Chocó in Colombia.

The Value of Narratives in Understanding Cosmology

The value of the narratives to western participant observers is that of all the many coding systems for cosmological knowledge, narratives are perhaps one of the most transparent and easy to access systems. Rituals, shamanic practices, music, even ethnobotanical procedures are so much more opaque and subject to more slippery interpretations. At least the stories can be translated into English or Spanish and their metaphors and relationships analyzed.

Assumed Knowledge – Layers of Meaning

Notwithstanding their apparent transparency, Emberá narratives are crammed full of assumed knowledge on the part of the listener. The stories articulate within a system of beliefs, a method of thinking about and encoding the nature of mind, spirit, social roles, culture, ecology and the cosmos.

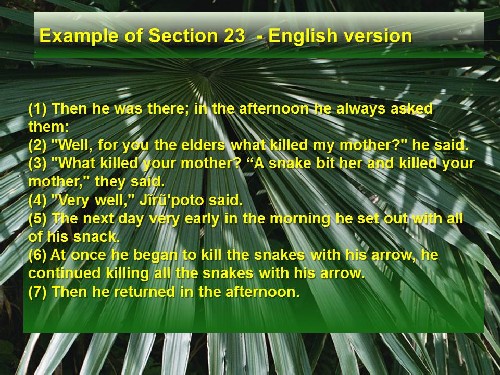

For example, when Alipio says “our father,” this is really Ancoré, a powerful creator spirit, and it is really most likely that the missionaries have insisted that Ancoré be interpreted as “our father.” And when Alipio states that the father spirit made love to the young woman between her toes, it is likely that many Emberá listeners are actually visualizing something like a crystalline, pale white beam of moonlight that pierces the thatch roof and enters the young woman’s foot to fertilize her with child. The Western assumption is most likely that of the image of male-female physical sexual intercourse between her toes. This is of course unsaid in this version of the story but almost every line is full of similar complex assumed knowledge in order to communicate its “pregnant” message. It is also interesting that the elders later on in the story tell Henupoto that the Moon killed his mother by sending a beam that consumed her heart. The irony is that, in part, this is true if the creator spirit fertilized his mother with a moonbeam that ultimately resulted in her death.

The woman becomes pregnant in the calf of her leg is symbolic. The calf of the leg is thought to be an indicator of strength. Traditional Emberá life requires great strength and endurance: work in the fields, trips to the forest, carrying burdens baskets of crops. I asked a middle aged man what makes a good wife. He told me. “Look at the calf. If it is strong and powerful, that is a good wife; if it is skinny and not muscular, not a good wife.” So the woman becomes pregnant in her calf, the symbolic source of her strength and a measure of her power and prowess.

Therefore, western listeners can only approximate the true semantic and symbolic significance of the narrative’s dramatic scenes.

It is similar in concept to the image of a western visitor on an Emberá hunting trip. The visitor sees a rainforest within a geographic and ecological context. The Emberá hunters see oh-so-much more, a complex interaction of natural, supernatural and animal spirit actors all conspiring to ensure or negate the opportunity for a successful hunt. The weather alone provides the Emberá hunter with a host of knowledge through which the hunter engages a complex playbook of where to go, what to hunt, how long to travel and many other relevant variables such as the likelihood for an encounter with a poisonous snake. Clearly, the spirits will let us know if we only listen correctly.

A small, seemingly insignificant bird call may have dramatic effect on the hunter’s senses even to the point of causing him to abandon the hunt and return home without delay and to hunt on another more propitious day. Of course, in our society specialized knowledge is highly heterogeneously distributed. The professional farmer sees far more detail in a country landscape then a city visitor because his vision is so tightly woven into his specialized knowledge of crops, weather, ecology, soil, micro geographic conditions and site and crop suitably. Any famer worth his salt could discuss for hours the implications of a single pastoral view.

Conclusions

And so it is with Henupoto that there are many layers of meaning. Quite frankly, I don’t really know what it all means. I only have a few fleeting insights as to some of the themes that are encoded in a story that has actively evolved for, most likely, centuries. And I have some Emberá language skills and many years to think about what this story and others like it mean. I do feel that the story transports the observer, both western and non-western, into another world deceptively hidden behind everyday life. We can peek behind the curtain of Western physical reality into the indigenous view of the universe. Certainly, there is not one or even a “correct” meaning to the story. I suggest it is more like a code that provides a vehicle for delivering Emberá cosmology and its attendant lessons in an easy to consume, and reproducible package with potentially many layers of meaning and interpretations. The elements of the code resonate with the consonant level of knowledge of the listeners. Like all good stories, each layer of meaning envelops and articulates with the personal experience, social and cultural matrix of the listener.

Certainly the story is entertaining to the assembled listeners. The importance of telling it well is evident, as the comments of the audience indicate. There are also those elements that are difficult to capture in text: the delivery, the onomatopoeia, the nocturnal context in which the night sounds are oh-so-close on that rainy evening in the Darién … all do not translate well in the written word. The story contains all the introductory conversation from the listeners and narrator that was on the tape to give a sense of how the listeners themselves approached the telling of the story, notwithstanding that some of the comments are embarrassing for the ethnographer.

It is interesting that throughout the entire story the Emberá are trying to get rid of Henupoto by providing him with impossible supernatural tasks that should end his life. But unlike many western stories where there is generally a resolution in the end, there lies a great ambivalence in Henupoto’s ironic role as he consistently executes the impossible tasks to avenge his mother and never seems to tire as the elders redirect him to his next mission even though he realizes that they had previously tricked him. All the while, as he rids the world of the most dangerous demons ,he himself is treated as a nuisance by the Emberá.

Bibliography

Harp, William, 1991, Ecology and cosmology: rain forest exploitation among the Emberá, Paper presented at Humid Tropical Lowlands Conference: Development Strategies and Natural Resource Management, Panama, Republic of Panama, June 17-21, 1991 and Published in Nature & Resources, Traditional Knowledge in Tropical Environments, UNESCO, Volume 30, Number 1, 1994, or on-line at www.trail2.com/ecology

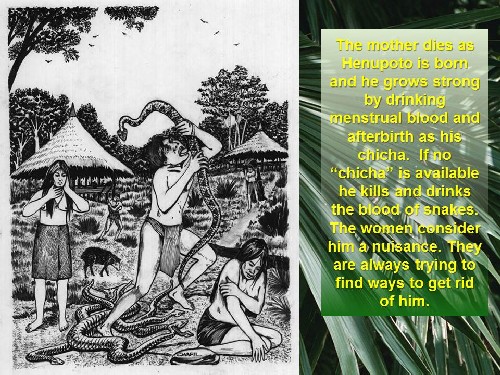

Here are the orignal texts of the Henupoto Story in English, Spanish and Emberá accompanied by the visual illustrated synopsis of the story in English.

Visual Synopsis of Henupoto (note size is 7 megabytes)

English Version of Henupoto

Spanish Version of Henupoto

Emberá Version of Henupoto

Story: Jĩrũ'poto (Henu Poto)

Narrator: Alipio Flaco, 26 June 1986, Pivasal, Pierre, Darién, Panamá.

Translator from Emberá to Spanish: Nilsa E. Castañeda, October 1990, Panamá, Panamá.

Translator from Spanish to English: Fiona E. Smythe, December 1990, Gamboa, Panamá.

Recorded, Compiled and Edited by William Harp, Anthropologist

Illustrations: Chafil Cheucarma

© Copyright 1998, William Harp, All rights reserved

Presented at the Double Session in Memory of Professor Emeritus Philip D. Young, Anthropologist and Mentor across Cultures

Chair and organizer: Carla Guerrón Montero (University of Delaware)

Society for Applied Anthropology 74th Annual Meeting

Hotel Albuquerque at Old Town

Albuquerque, New Mexico

March 18-22, 2014

This story can be reproduced in part or in whole for non-commercial purposes as long as the attribution information above is included. Any use without the inclusion of the attribution information is strictly prohibited. The story may be shortened but must not be otherwise edited. The drawings by Chafil Cheucarma can be used only by written permission of William Harp. Any other interests please contact William Harp (harp@trail2.com)

An asterisk (*) is used to designate an unknown person, unknown information, phase not translated or onomatopoetic sounds.

Translator’s comment: The conversation of those who were there before the telling of the story

Section 1

"Story of Jĩrũ'poto," said *.

"Alipio, aren't they talking to you?" Teresa said.

"Hey!" Alipio exclaimed.

"They are talking about the story that you know," Teresa said.

"Ah..! The Jĩrũ'poto story," said Alipio.

"The story of Jĩrũ'poto, son of Jĩrũ'poto," said *.

"Mama, you tell the story of Jĩrũ'poto," Alipio said.

"You know it, you tell it," the mother said.

"Once again I am going to put my feet upon you..ha, ha," Lucia said.

"But why..! *

"YY...but this one is already my husband...ha, ha." Lucia continued to laugh.

"They are going to hit you for that from now until tomorrow, you will see," *

"The story of Jĩrũ'poto,...tell it then," said *.

"Tell it, even if you do it badly," Teresa said.

"Tell, tell, I am going to listen to you lying down, but I am going to sleep," * said.

"It is going to be difficult if it is in our Emberá language, for he is not going to tell it in Spanish," the mother said.

"I like it if you listen carefully to my story," said Alipio.

"Well, begin to tell it, for we are not only going to listen to you," * said.

"This one, I am going to say first to start," said *.

"Listen," Teresa said.

"That Emberá always went to the mountain," *.

"Is that how it starts?" * said.

"That boy always went to the mountain... he is talking about the one who killed Bambero, after the shaman bewitched him," Alipio said.

"That can also be told, but haven't you been telling Jĩrũ'poto up there?" the mother said.

"Yes, like Taichita was telling it," Kulioli said.

"First, let one tell it," said the mother.

"Ay...this mosquito comes to bite one's eye," Teresa said.

"Ayy..!" *

"That mosquito just broke his teeth...ha, ha" Lucia said.

"Lucia, will you shut up," Kulioli said.

"Put that lantern way over there," * said.

"It is alright there," Lucia said.

"It is lighting one's face," * said.

"One's face is not so pretty, it looks like the face of an squirrel," said *.

"Yes, he still has a tearful face," Alipio said.

"It would not be Cristina seated here," Teresa said.

"She is going to mention the other one," Lucia said.

"Does he already have it lit?" Alipio asked.

"I think that he still has not lit it," Teresa replied.

"Ready!" * said.

"Ha, ha, ha...still," Alipio replied.

"Ready for the picture," Kulioli said.

"They say that he also killed the Nusí," Alipio said, as though asking.

"Then tell the story," said *.

"Well he has to start from the beginning until the end," the mother replied.

"He was killed by the Geambuima," Alipio continued to orient himself.

"He was killed by the Geambuima, your dead father used to say," Alipio's mother said.

"Yes..." Alipio replied.

"Well, tell the story," * said.

"He wants you to tell the story in the Emberá language," * said.

"Of course...kake," *.

"He wants you to tell the story in our language," said Lucia.

"Listen to Lucia," said Kulioli.

"But my mouth is getting dry," Alipio said.

"So, go and get water, he is thirsty and that is why he is speaking this way," Teresa said.

"Now we are going to start," * said.

"And you...the dog...I do not know where it is," Lucia said.

"This, if not the bone of the turkey hen," Teresa said.

"Yes...ha, ha," Lucia said.

"This, if not the head of the white faced monkey," said *.

"The head of the white faced monkey, so that one's chest come well," the boy said.

"Did you find it?" Lucia said.

"Of course," * said.

"Miki is lying face up," Lucia said.

"Who?" the girl said.

"She is *" Alipio said.

"Like she is lying face up," Teresa said.

"Who are you talking like that about?" Miki said.

"You," Teresa said.

"Tell it then," the boy said.

"Why are there so many kids here...I am going to spit in all their faces right now...ha, ha," said Alipio.

"But tell the story," * said.

"Did you forget the story?" * said.

"He is asking you if you forgot the story," Lucia and Teresa answered.

"I am thinking carefully now," Alipio replied.

"Okay," said *.

"But he wants you to tell the story of Jĩrũ'poto," * said.

"Yes, that is the one that he wants to record on the tape," Alipio said.

"Mother, the woman who our father made love to between the toes, she was our mother, right?" Alipio asked.

"In this day; where was it that he was telling the story? Where were you telling the story?'" * said.

"The same, and here," Alipio's mother said.

"He was telling the story there and now is asking again," said.

Alipio's mother introduces:

Section 2

(1) They say that our father made love to woman between her big toes; right here, here he made love to her (she said pointing between her toes).

(2) After our father did that she suddenly became pregnant: here, here (she said pointing to her ankle).

(3) After, when she gave birth, the mother died from the pain in her leg.

(4) Then he grew, since he was the son of our father he grew very quickly.

(5) Then, since he lived among the women...[as I am living with her), like Tocayo, he began asking her:

(6) "Aunt, for you who are already women, what killed my mother," he asked her like that.

(7) But then he; just like you who are waiting for a baby, he was waiting for that.

(8) That is why they hated him, because he wanted to drink that blood...

(9) "He wanted to drink that blood?"...he requested the blood especially when they gave birth.

(10) "You can collect it for me in a gourd," he said.

(11) He also drank the water that had blood in it when the women had washed their vaginas.

(12) But then, since they wanted to kill him, she said to him: "The Nusí that is down there killed your mother."

(13) He killed that Nusí.

(14) "When he was shrimp fishing?” … Of course; thus he threw his dead father...

(15) Well, he already knows that story and so is telling it badly.

Section 3

"He says that that is what he is learning," Alipio's mother said.

"Like Jĩrũ'poto?" Alipio asked.

"Yes that is what he is learning is like, well, that is what you have heard that he is studying," his mother replied.

"Ay...I have a bad cough," Alipio said.

"Show him; for it is not just today that I am teaching the word and now it is your turn," the mother said.

"Yyy..." Alipio said.

"For the house," said * .

"He gives all that to us as though it were free, but those things are very expensive in the city," the mother said.

"About twelve dollars," Alipio said.

"Start to tell it then!" said * .

"Ho! It would not be a chore!" they replied.

"Although it may always be badly," the mother said.

"Give it although it may be half twisted," Teresa said.

"Listen, listen quietly," Teresa said.

"He is telling it," Alipio said.

"Now he is going to tell," a child said.

"Aha...he is waiting for you," said *.

"My face is very lit up, I am going to go back here," Alipio said.

"Hurry, he is waiting for you," Teresa said.

"For you to tell it," Lucia said.

"I will tell this when I am alone, in the crowd I have not told it, sirs," Alipio said.

"And when are you going to learn to tell a story in a crowd?" Teresa said.

"It's a lie, it's just that he is like that," Teresa said.

"They should have made him buy a cigarette to smoke while he told the story," Alipio's mother said.

"Hurry Alipio!" Teresa said.

"Well, Lucia has some," a child said.

"I am going to go to sleep," * said.

"Well, let's tell it badly then," Alipio said.

"Of course, I have been telling you to tell it, even if it is badly, if it is in our Emberá language, how are you going to tell it badly," the mother said.

"Does he have it ready?" Alipio asked.

"Okay, okay, it is ready then," said *.

"Everyone be quiet now," Teresa said.

"Start, meanwhile the curiosity is going to leave him, no?" Teresa said.

"Then we are going to tell a story," Alipio said.

"Well, who is going to be the one who replies? Him, then," said *.

"I will, I will, I will," the boy said.

"Enough!" the mother said.

Section 4

(1) Our father had a woman; she was his wife.

(2) Well, our father made love to the woman between the big toes of her feet.

(3) Making love thus to the woman, between her toes, suddenly she became pregnant in her calf.

(4) Here, on the leg of the woman, she was pregnant in her calf.

(5) Thus, in that state of pregnancy, when the moment to give birth came; her calf split open and she gave birth.

(6) Being thus, the woman died from the pain.

Section 5

(1) Well, being thus; there, there the child grew quickly, because he was the son of our father.

(2) After he grew quickly, when he was already a big young man.

(3) Then he asked the elders and the women.

Section 6

(1) Being thus, since the child was young, when the women had their menstrual cycle

(2) He asked for the woman's blood like asking for corn beer.

(3) Asking for that thus, if he did not drink that beer he felt ill.

(4) That is why the women were angry with him, for being like that.

(5) When the women had their period he asked the women at once: "Is there beer?", he said.

(6) At once the women went to the river, they washed, they washed, they washed their vagina in a calabash gourd.

(7) At once they gave it to him to drink and he drank it.

(8) That is how he lived, that is why nobody wanted to be around that guy.

Section 7

(1) Well, the guy always asked...

(2) "Was it good to clean oneself and give him that of nowadays?"..

(3) To the elders: "Well, you the elders, what killed my mother?" he said.

(4) Then they answered" Your mother?

(5) You want to know?

(6) How did you mother die?" he said.

(7) Your mother was shrimp fishing in order to feed you and the Nusí that lives down there ate her," he said.

(8) "Show me were that Nusí is that is good." he said.

(9) “So it was that Nusí that ate my mother."

Section 8

(1) At once they truly went on tiptoe without making any noise; "There it is," they showed him.

(2) That Nusí could sense even a little bit of noise.

(3) Well he was there, being thus the next day, after they showed him, he went.

(4) Well, the guy truly killed the Nusí, after he killed the Nusí he came.

(5) The next day, in order to get rid of the Nusí, a huge rainstorm fell for three days.

(6) That growth of the river that came was very big and it nearly killed the people for once and for all by flooding; once again without wanting to … for having killed.

Section 9

(1) Then, being thus, he always continued asking for his beer.

(2) Whenever a pregnant woman was about to give birth, he stayed there, waiting and waiting.

(3) He went to dive for fish, he gave her all kinds of food, fine, until the moment of giving birth arrived, at the moment of birth he went under.

(5) Then he drank the blood that gushed forth.

Section 10

(1) Being thus:

(2) "For you the elders, what killed my mother?" he asked.

(3) "You want to know?" he said. "What killed your mother?"

(4) "Down there, where the huge, deep pool that appears infinite is."

(5) "Your mother was shrimp fishing on the bank there, and then... the Ge swallowed your mother," he said.

(6) "The Ge swallowed your mother," he told him.

(7) Whereupon: "Really!" he said. At once: "That is very good," he said.

Section 11

(1) He tied some balsas (Ochroma pyramidale) together.

(2) After he finished with the balsa (raft) he got; plantain, a frying pot, boiling pot, salt, and a match, he took all those things; an oar, his knife and he went with all of his bedding too.

(3) Well, he made some *carrizos* at once.

Secion 12

(1) Then truly from up there he came down the river.

(2) Well, at that time the rest of the people were watching from a hill, watching Jĩrũ'poto going down the river on top of his balsa.

(3) Whereupon... the he sounded the *pipano* (small flute) that he had made; *pure*, *pure*, *pure*, he went down river.

(4) After a little while he did it again *pure*, *pure*, *pure*...

(5) Well he went downriver and make a dogo*?.. He went down river and made a dogo*.

(6) Truly, in one second the Ge sucked him down.

(7) When he arrived at the middle of the deep lake, before the eyes of the others were watching, the Jĩrũ'poto began to spin in the water that was made into a whirlpool and he went inside with his balsa...

(8) "Only his feet showed!"..., Jĩrũ'poto went down inside with all of his balsa.

(9) Whereupon, the others who were watching: "Hey! Today Jĩrũ'poto really did die," the said.

(10) "Today that dick really did die, now he will not bother us anymore," they said.

Section 13

(1) Well, when he arrived in the stomach of the Ge he saw a river running with a beach...

(2) "In the stomach?" Yes, in the stomach; dwarf bananas, plantain, banana, square shaped plantains, was all there.

(3) Macaws, parrot, duck, for once and for all, there was everything.

(4) There was a huge quantity of firewood, whole bunches of firewood.

(5) Well, when he looked carefully there were two Emberá; a woman and a man were in the stomach of the Ge and they were very pale.

(6) Whereupon he looked up.

(7) ****

(8) *****

(9) At once he saw the heart of the Ge hanging in the air and beating.

Section 14

(1) He went to see the entrance of the river.

(2) Then he picked up some firewood and made a fire on the beach..

(3) He also had his balsa there tied in the river.

(4) Well, then he came and he cut the heart of the Ge...

(5) "And he did not feel it?"...he did not feel.

(6) As soon as he cut the heart of the Ge he began to drink the blood from above.

(7) He is drinking like this...

(8) "And did he also drink the blood of a fish?"...he drank the blood of the Ge.

(9) In one blow he opened the heart of the Ge and cut it in very thin strips.

(10) Then he skewered it on some twigs and put the meat on to cook.

(11) Well, he ate the heart of that Ge.

(12) Well, he gave those pale Emberá that were there inside something to eat.

Secion 15

(1) Well, Jĩrũ'poto asked them:

(2) "Has it been a long time since you came here?"

(3) "It has been a long time since we came," the answered.

(4) "It being thus, why have you not left?" he asked.

(5) "How can we leave, we are in the stomach of this animal, how could we have left?" they said.

(6) "Do not worry, for we are getting out," he said.

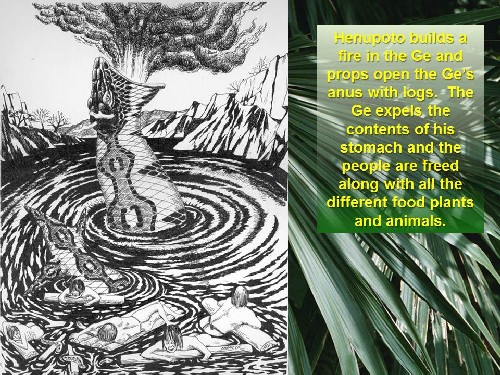

Section 16

(1) He said this once and for all.

(2) The next day, truly he began to remove all the sticks that were in the part of the anus.

(3) Then he put a stick in the anus of the Ge so that it would stay open.

(4) The next day he got onto his balsa.

(5) "But hold on tightly," said Jĩrũ'poto.

(6) Then at once the others held on tightly and they went out.

(7) They went out in the middle of the river.

Section 17

(1) When he was eating the roasted heart of the Ge;

(2) At that moment smoke came out of the middle of the river and expanded a little bit over the surface of the water.

(3) Whereupon the other elders said:

(4) "That dick Jĩrũ'poto has not died, because a little bit of wood smoke appears on the surface of the water."

Section 18

(1) Suddenly Jĩrũ'poto appeared.

(2) As soon as he appeared he started again: *pure*, *pure*, *pure*; but nobody saw him even though he was *salomando* on his balsa in the middle of the huge and deep lake that appeared infinite.

(3) The came toward the bank rowing, rowing until they reached the bank.

(4) On those gira (Socratea exorrhiza) roots that are close together and *tupido*, right?; well, Jĩrũ'poto began to go into those roots and then he came out again, running, he went in and out with great ability.

(5) Whereupon Jĩrũ'poto said to them: "Do what I am doing, if you do not do what I am doing you will die soon," he said.

(6) Whereupon the Emberá said: "Ay, ay uncle those gira roots are going to scratch us badly.," he said.

(7) "Of course not, that will not scratch badly," he said, "Can't you see that they have not scratched me at all," he said to them.

(8) He went ahead, jumping and turning.

(9) Then it took him.

(10) A week later the Emberá died, all the Emberá died.

Section 19

(1) Then: "Well, and my beer?" Jĩrũ'poto said.

(2) Then he was looking upward, he himself.

(3) "Aha... look at Jĩrũ'poto, who they said had died, how did he not die and that Jĩrũ'poto has come again to bother everyone else again?" they said.

(4) No sooner had he arrived, than he was asking for his beer.

(5) The women went to the river at once and washed their vaginas in a calabash and gave it to him.

(6) He drank that...

(7) "Well, if they did not wash themselves like that, could he die?"... He could starve to death.

(8) If there was no beer he could die...

(9) "He did not eat?"... Of course not, even if he ate that was like his beer.

Section 20

(1) Then he was always asking:

(2) "Well, for you the elders how did my mother...well, now tell me the truth," he said.

(3) "What killed my mother?"

(4) "What killed your mother? This killed her... that thing that is on the mountain that looks like a big rooster that has a yellow nose, that kicked your mother and pecked her to death," they said.

(5) "That is very good if it is true," he said.

Section 21

(1) Well the next day he began to make the point of the arrow; ten, ten, ten, he spent the whole day doing that.

(2) Well, as soon as he finished making it he tried his arrow on a great big espave (Anacardium excelsum) tree.

(3) He pulled the arrow and he let it go and it went right through the middle of the espave tree.

(4) "Well, now it is good," said Jĩrũ'poto.

(5) The next day, after he had finished making the arrow.

(6) Well, he went to the mountain, he went walking.

(7) He went in the morning, when he returned in the afternoon, Jĩrũ'poto came but he was not carrying a bird.

Section 22

(1) Well, the next day in the afternoon, at night:

(2) "Well, today you had better tell me the truth," he said.

(3) "What killed my mother?" he said. "What killed your mother?

(4) This killed her...that which they call the pava (Crested Guan, Penelope purpurascens, or tusí in Emberá), that which has yellow paws, that killed your mother and ate her," they said.

(5) "Your mother was cutting Panama hat palm (Carludovica palmate), and one that was under the Panama hat palm plant bit her and killed her," they said.

(6) "Very well," said Jĩrũ'poto.

(7) He did the same as before and once again he left.

(8) When he returned he was carrying the same as before.

Section 23

(1) Then he was there; in the afternoon he always asked them:

(2) "Well, for you the elders what killed my mother?" he said.

(3) "What killed your mother? A snake bit her and killed your mother," they said.

(4) "Very well," Jĩrũ'poto said.

(5) The next day very early in the morning he set out with all of his snack.

(6) At once he began to kill the snakes with his arrow, he continued killing all the snakes with his arrow.

(7) Then he returned in the afternoon.

Section 24

(1) Well, he continued there:

(2) "Well, for you the women, for you the elders, my mother...today you better tell the truth," he said, "How did my mother die?"

(3) "You want to know how she died? Your mother was killed by that which shines up there, that which is lighting us, that was what killed her," they said.

(4) "That which they call moon was what killed your mother, when she was sleeping, right then it reflected directly into her heart and all at once it ate your mother's heart." they told him.

(5) "Very well," he said. "Very well, since that dick killed my mother, it being thus, early tomorrow we are going to get to know each other," he said.

Section 25

(1) Well the next day in the morning he pulled up a tender bamboo shoot.

(2) After he pulled it up, he replanted the bamboo.

(3) Then he began to hit the bamboo, saying: "Let it grow, let it grow, let it grow, let it grow."

(4) When he said that the bamboo began growing long and thin.

(5) Until it arrived at the moon.

(6) "That's enough!" said Jĩrũ'poto.

(7) Well, Jĩrũ'poto went up at once.

(8) Even then he did not stop drinking his beer.

(9) Well, then he kept climbing upward.

(10) "Look at me," said Jĩrũ'poto.

Section 26

(1) Jĩrũ'poto went on climbing up little by little in the bamboo...

(2) "Did he go quickly?"...Aho! How could he go slowly, he also went very quickly.

(3) Until he reached the moon above, since the bamboo reached it.

(4) When he touched his hand right on the face of the moon to see where he could grab best.

(5) Then, when he touched the moon like that, on the earth they said:

(6) "Go on! go on anteater son!" they said. "Because if not, Jĩrũ'poto is going to pull the moon out and throw it down," they said.

(7) When he was touching it with his hand, the armadillo began to gnaw, to gnaw the bamboo.

(8) Whereupon: "Go ahead woodpecker, my son, you are truly real," he said.

(9) The woodpecker began to hit with his beak, *ton, ton, ton* on the bamboo and... *pos*! It broke.

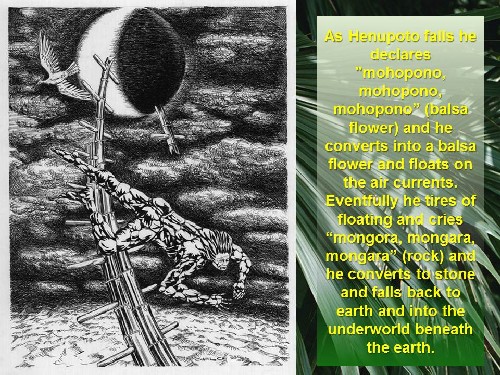

Section 27

(1) Then, since it broke where he was hanging everything fell downwards.

(2) Well, then he said: "Balsa flower, balsa flower, balsa flower,” and he was turned into a balsa flower.

(3) Well, thus he stayed suspended above and he flew in the air.

(4) He stayed flying like that in the air for a long time.

(5) It would look as though he was coming in low and then the wind would take him upwards once again.

Section 28

(1) Then the elders said: "Now surely Jĩrũ'poto has died," they said. "Now Jĩrũ'poto has truly died up there," they said.

(2) Whereupon the other elders said: "Men, that thing that you see that flies like a white balsa flower, that falls and rises with the wind, that is Jĩrũ'poto."

(3) "How could that be Jĩrũ'poto, Jĩrũ'poto died, today was truly the end of him," they said.

(4) "He died," the women declared.

Section 29

(1) Well, he got tired of being up in the air for so long.

(2) Then he said: "Rock, rock, rock," and he turned into a rock.

(3) From up there he came and *truummm*! he went right through this earth and kept on going.

(4) At once he arrived where the Amurukos are, that is where he came out.

(5) He arrived in the morning and at the spot where he fell, he got up and went towards a house.

(6) Once he had been in the house for a while, they began to prepare and cook his meals.

(7) Then they served him the food, Jĩrũ'poto began to eat at once and to swallow the food down.

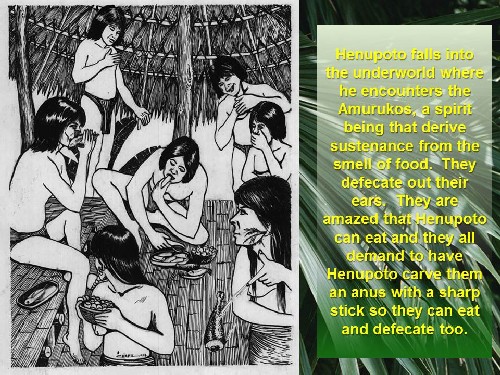

Section 30

(1) Whereupon they said: "Jĩrũ'poto died, now he really, truly died."

(2) While, at that time he was eating calmly.

(3) But at that time he was observing that the Amurukos inhaled, inhaled deeply with their noses the steam that came from the hot food.

(4) When the children were eating like that, the little ones began to expel the excrement when they hit them lightly on the ears.

(5) It was like the excrement just came out of the ears.

Section 31

(1) Well, being there in front of the rest of them who were watching, Jĩrũ'poto began to expel excrement from his anus.

(2) Well, at that time a boy who was nearly a young man asked him:

(3) "Hey Uncle, why after you eat do you begin to defecate? How do you begin to expel excrement from your anus?" the boy asked.

(4) "Well, because I am like that nephew, I am that type of a person," he replied.

(5) "Hey, nephew, why are you like that," he said. "You breathe in through your nose and defecate from your ear? Why are you like that?" Jĩrũ'poto asked.

(6) "Uncle, we are that type of person," he replied.

(7) "Nephew, I am going to experiment, let me see your anus," he said.

(8) When he went to touch the anus of the boy, he sounded like the paper-thin skin of an onion, that is how thin it was...

(9) "The anus was covered?"..., yes, the anus was covered and it sounded like a paper.

(10) "Nephew, I am going to try," he said.

Section 32

(1) Then he took a knife and he began to slowly and carefully open a hole in the very center of the anus until he opened it.

(2) Then he went diving for fish to feed him so that he would swallow it down.

(3) "Nephew, eat this up," he said to him.

(4) The boy truly ate it up with determination.

(5) "Chew it well and swallow it down," he said to him.

(6) It was true that the boy began to eat and eat.

(7) Whereupon he said: "Tell me when you feel the desire to defecate; here in your navel, under the navel, if it hurts you there then tell me nephew," he said. "So that we can go and defecate."

(8) The boy told him, "Uncle, it hurts me here," he said.

(9) Well, at once he said: "Let us go to the river, as soon as you defecate that pain will leave you, when you get to the river, push hard," he said.

(10) When they arrived at the river, he pushed hard, and truly he began to expel excrement just like him.

(11) Then that boy began to eat all sorts of foods.

(12) Well, he opened the anuses of all the people of that house, for all of them.

Section 33

(1) Well… Whereupon a bat bit a child, since it was night then; when it is night time here we are all sleeping.

(2) But at that time there where the Amurukos are at this time it is daylight.

(3) Then those who are walking are in bed when here it is day it is night there and they are asleep.

(4) Whereupon, in front of Jĩrũ'poto, who was watching this, a bat with a big hat on came and bit everyone.

(5) At once, ay... that bat bit them, he bit them and so they turned on the lamps; that is how they were.

(6) Whereupon one could also see everything that the men did who were seducing the women.

(7) Well, at that moment, when Jĩrũ'poto lay down to sleep because it was night time for us, the women bothered him, jabbed or tickled his eyes.

(8) The women jabbed or tickled his eyes, and that is why they laughed.

Section 34

(1) Well, being thus; he went opening their anus; sometimes he would open it too much by mistake.

(2) For having opened too much they died.

(3) So he was living like that, opening the anus.

Section 35

(1) Well, being thus, all at once they said: "Ay...the soldiers are going to come soon, the soldiers are coming soon," they said.

(2) Jĩrũ'poto was worried about the soldiers: "Ay...if they come with a rifle, now I will really die," he said...

(3) "Peluchito"?*

(4) At that moment when they were thus, suddenly one passed them running upwards:

(5) "The soldiers are arriving down there, the soldiers have already arrived down there," he said.

(6) Truly at that time all the people took off running.

(7) "Ay...uncle the soldiers are coming, ay... those soldiers are very scary," the boy said. "Hide uncle," he said.

(8) "I want to go and see what they are like: Do they shoot rifles?" he asked.

(9) "Mister, those are soldiers, ay...Mister they will kill us," the boy said.

Section 36

(1) The back of the one who was telling him was all scratched and he ran upwards screaming...

(2) "Ha, ha, so he was like that."?

(3) Well, being thus, the path downwards looked like a highway.

(4) When he looked down: some people were coming up who appeared masked? (*caratos*) and had red faces, a great crowd came up the highway so that the whole path looked black.

(5) Well, until they arrived under the house and at once they began to surround the house.

(6) Whereupon one of them jumped from the ground up over the house and the others immediately began to arrive, flying above.

(7) As soon as they arrived the attacked with their beaks, they pecked him and stepped on him, they were the *perromulatos*. (Odontophorus gujanensis or Marbled Wood Quail)

(8) They screamed: "Ay...ayayay, uncle, ay...help me uncle," they said.

Section 37

(1) At once the *perromulato* went to him, to peck, and there he grabbed him by the head and smashed the shithead *perromulato*.

(2) "Ah...these are the soldiers?" he asked. "Now they'll see," he said.

(3) Immediately he took a faggot from the fire and began to whip, he went whipping them on the *rape* with the faggot.

(4) All at once they had their paws, their wings broken, others that he grabbed by the head died.

(5) Well, he hit them wherever he grabbed them and threw all down from the house.

(6) Then they went running down, Jĩrũ'poto jumped to the ground and ran behind them whipping them, whipped he took them until he let them go a little bit above the other house.

(7) All at once he picked three or four of the *perromulatos* up, he prepared them well and he ate the *perromulatos*; he ate the soldiers.

(8) "Nephew, is this a soldier?" Jĩrũ'poto said again.

(9) "This is not a soldier, this is food; in our land we call these *perromulatos*," he said.

(10) "These kill us, uncle," his companion said.

(11) "What could this kill, you are crazy, how could this kill us," he said.

(12 ????????????

(13) "The soldiers in my land fire rifles and kill with rifles; that is what soldiers are like," he said.

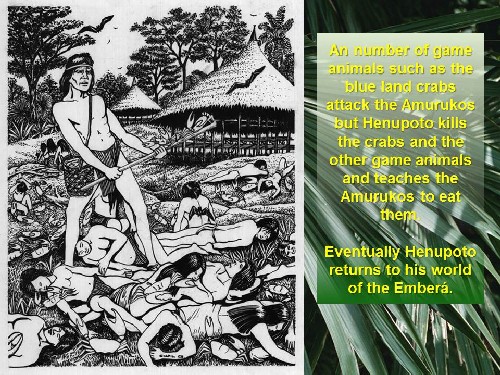

Section 38

(1) Well he was there, being there suddenly:

(2) "Ay...the soldiers are coming soon," he said. "Ay! These soldiers really are more dangerous," he said.

(3) "I am going to wait," he said. "Let's see what kind of soldiers those are, the soldiers that are coming," he said.

(4) Well, suddenly one ran upwards screaming: "The soldiers are coming, the soldiers are coming, go and hide yourselves," he said screaming and he passed by running.

(5) Whereupon, when he looked downward: ay! all of those of the blue backs (most likey Cardisoma guanhumi or Ucides occidentalis, two species of large land crabs) were coming up.

(6) Only blue backs could be seen and the white of the hands.

(7) When he looked carefully; it was the crabs that were coming in droves.

(8) Whereupon the crabs in the column...

(9) "Whereupon the children were in the batea ( a large wooden platter or wooden bowl)?"..., whereupon it was true, the little children like this *Kulioli*, all the children that were small like him.

(10) They put them in a very big *batea* and others in the *jorones* (large ceramic jugs).

(11) When that happened the elders hid themselves, other elders were running outside, they went running.

(12) When that happened the crabs climbed up the column and at once they began biting people, having bitten them they died right away from that like...

(13) "The people?"...The people, the Amurukos died.

Section 39

(1) One crab, big and with a white hand; that went to attack and bite Jĩrũ'poto and he gave him a kick and it went rolling.

(2) At once Jĩrũ'poto dragged a faggot from the fire; with that he went whipping the *rape*, all that were in the house had their little feet broken and their *caprazones* came out.

(3) He passed the faggot at once down the column to the *rape*.

(4) He jumped to the ground: whereupon he went down to the path, ay...

(5) "That is why they did not climb up?” That is why they did not climb up.

(6) They went forth from there back to where they came from in great groups.

(7) Whereupon Jĩrũ'poto followed behind them with the faggot whipping them *rape*, with the *rape* he went taking them like that until he left a little bit beyond the other house.

(8) Some of them went, some of them were hidden in the middle of the path and they came running down and he hit them with the faggot *poo.*

(9) He killed nearly all of them, but many of them escaped down the hill.

(10) Well, he picked up four of the biggest crabs, after he picked them up he put them on to cook with Platano sancochado (plantain soup), a stew (tapao).

(11) After that if you see, then truly come.

(12) "These are soldiers?" he asked. "These are crabs, we eat these in my land," he said.

(13) "How could this be a soldier, you are saying that a food is a soldier," he said.

Section 40

(1) Well, time passed there; being thus he passed the time opening the anuses of the others; sometimes he opened them too much.

(2) When the bat bit some of them, he gathered them together with the ashes of the fire.

(3) For those bitten by bats; they have a very big hole excavated.

(4) Whoever was bitten by the bat, they dumped there in that hole the next morning.

(5) Whereupon he raised them, took them out and put them with the ashes of the fire and they were healthy again.

(6) Being thus he said: "This bat can be killed." "And are they bats?" he asked. "It would be easy to kill that bat," he said.

(7) "Ay...mister," they said like the women from here.

(8) "Please, kill that bat, you can kill that bat," they said.

(9) "Very well, I am going to kill that bat," he said.

Section 41

(1) Whereupon some who were romancing (galanteando) began to speak.

(2) Then the men that the women did not like left.

(3) Some, which the woman accepted stayed there sleeping, right there, right away...

(4) "Right there?"...Right away, right there they took the woman...

(5) "Yy...it was night time you understand, no?"..., because it was night time you understand.

(6) Since it was now night some went hunting with their dog.

(7) Some went with their dogs and rifles...

(8) "Truly, it was a good thing to give that one a *caparazon.*” (editors note: maybe this is a shell)

Section 42

(1) Well, when he looked truly the bat came climbing up, with his big hat the bat came climbing up.

(2) He took a faggot from the fire and he sat down to wait, ready.

(3) When he was going to bite, right then Jĩrũ'poto hit him *poo, poo*, he went hitting him, and he killed the bat.

(4) Whereupon: "What, what bat, bat," they said.

(5) Immediately they lit the lamps and left them with the light on.

(6) "Well done, that bat that bit us will not bite us anymore," they said.

Section 43

(1) Well, he continued living there.

(2) Well, once again: "Ay the soldiers are coming, ay these soldiers really are very dangerous," they said.

(3) Some are red, some black at the same time with a yellow nose, the yellow ones are those that have the hats on," he said...

Section 44

(1) "The lieutenants?”... “Aha, at once...”

(2) "Coronels?”...”The lieutenants!”

(3) "Well, there are different kinds of soldiers," they said. "These soldiers are very dangerous, those soldiers are really only ones that are most dangerous," they said.

(4) Truly, suddenly, the messenger passed by running upwards and screaming.

(5) He had his whole back...

(6) "He was escaping then?"...Scratched, scratched with the nails, he was bleeding from a wound and he went upwards screaming...

(7) "He was running and screaming?" He was running and screaming:

(8) "People, the soldiers are coming, the soldiers," he said. "Hide yourselves," he said.

(9) When they said that immediately they began putting the babies and the children in the large wooden platters (bateas).

Section 45

(1)Jĩrũ'poto remained seated.

(2) When Jĩrũ'poto looked down at the path: ay... it was like the pavos and the pavas (Great Curassow, Crax rubra).

(3) The pavos came climbing in a huge multitude all at once: *piii...papapapapapa*....they yelled and came up the path straight towards the house.

(4) Then, from the ground, *papapapa*... they arrived at the house, *piii...piz, piz, piz*, the big male *pavo* said.

(5) At that moment that one began to scratch with his claws, he packed and kicked the other people...

(6) "They?"..., the pavos and the pavas were very large.

(7) The female: *kon, kon, kon*, she said all at once.

(8) All at once they pecked and kicked and scratched everyone.

Section 46

(1) Immediately a very big male that had a yellow nose.

(2) That one went to where Jĩrũ'poto was seated to peck and kick.

(3) Right there he grabbed his *pascuezo* and smashed him against the column...

(4) "Ready?"..., ready!

(5) Then truly, he dragged a faggot from the fire and went hitting them *po, po*...

(6) "That is why the people of that house did not die?"..., that is why they did not die.

(7) Whereupon some went with their wings broken, some had their necks broken, others had their thighs broken.

(8) He threw them all down to the ground at once...

(9) "He threw them down from there?"... From there, he did not let them come up.

(10) After he sprang to the ground he also followed them *po, po*, he went killing the soldiers.

(11) Some went with their thighs broken, he hit them wherever he could, some that came running down, right there, *po*... he went killing and others went to the bush.

Section 47

(1) Well, he was there; he grabbed to of the biggest pavos, after he skinned them he made stew (tapao)...

(2) "He made *rebano*?...He made a soup.

(3) Then he gave everyone something to eat.

(4) "Is this soldier?" he asked. "Where I live they call this pavo, pavo, he said.

(5) "How could this be a soldier," he said...

(6) "At that time did all the people in the house defecate?"...Yes, he gave everyone something to eat after he opened their anus.

(7) He was there opening the anuses of the rest of them.

Section 48

(1) Well, he was there, there.

(2) "Well men, I am also leaving, now it is time," he said.

(3) Suddenly, the next day in the morning he came back to where he lived...

(4) "Listen to him!".

(5) "Look at Jĩrũ'poto; they had said that he had died, and here he come again," they said. "That Jĩrũ'poto is coming up the hill," they said.

(6) Then he arrived: "Hello people," he said. "Well, isn't there any beer for me?" he asked.

(7) Immediately they gave him the chicha to drink.

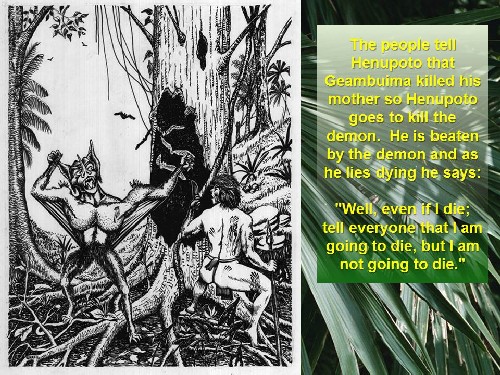

Section 49

(1) Well, there he was.

(2) The next day in the afternoon he asked: "

(3) "Now, now truly for you the elders; tell me the truth," he said. "What was it that killed my mother? Now really tell me the truth, what killed my mother?" Jĩrũ'poto asked.

(4) "What killed her? Up there, up the river, the thing that they call Geambuima, that is what killed your mother," they told her.

(5) "Ah...show me," he said.

(6) Immediately they went to see, slowly.

(7) Well, when they arrived to see it was asleep.

Section 50

(1) Whereupon the next day they told him: "When it has its eyes open; it is asleep," they said.

(2) "When it has its eyes closed; at that moment it is awake," they said.

(3) "Really?" he said.

(4) Immediately he began to make arrows and he finished making six arrows and a bow.

(5) We Emberá would not be able to lift that bow that is how heavy it was.

(6) "This bow is very light," Jĩrũ'poto said.

Section 51

(1) They next morning he went.

(2) Whereupon the others stayed watching him from the bush...

(3) "He was very strong?"...they continued watching from the bush.

(4) Ho! Truly, that thing they called Geambuima was in the middle of the river.

(5) It was standing on four legs in a very pretty place and it had its eyes shut.

(6) Whereupon Jĩrũ'poto began to stretch the arrow in the bow, trying out the arrows.

(7) After he had been stretching and trying it; he let go, the arrow went flying (rozando).

(8) The direction of the arrow could not even been seen.

(9) At that moment the Geambuima lifted itself in flight; *buurrr*... it began to fly all over the place.

(10) The wings were like the edge of a knife.

(11) And it truly began to fly, *buurrr*... on top of Jĩrũ'poto.

(12) Then Jĩrũ'poto had his chest on the ground and he *esquivaba* with the arrow.

(13) Then being in that condition, Jĩrũ'poto shot the arrow upwards, he continued shooting.

(14) When he had one arrow left he said: "Ho! Today I am truly going to die," he said.

(15) "But even though I will die, I am not going to die," he said.

(16) "I will turn into different types, in an instant I will turn into blood suckers."

Section 52

(1) At the last minute he shot the last arrow; he was left without arrows.

(2) "Well, even if I die; tell everyone that I am going to die, but I am not going to die," he said.

(3) Then, yes, he held it off with the bow for a little while.

(4) Then he threw it and it went very far.

(5) He went there and threw it, once again he went there and threw it.

(6) Jĩrũ'poto, being in this situation, cut his throat.

(7) At once, when the head of Jĩrũ'poto was cut, the one they call Geambuima trapped it with its snout and went to stand where that Geambuima had been before.

(8) So, holding him bitten like that he began to turn into: bats...

(9) "Bat?", Bat then, *tabanos*, *kichikichi*, flies, mosquitos, *jejen*, *mochiquita*...

(10) "Morrokoi?". He began turning into all of that and also into *tobaroba*, whereupon he turned into them.

(11) He turned into all kinds of insects that only suck blood.

(12) When he had bitten him he completely disappeared.

(13) And that is how it was!

|

|